*1972 (Slovenia)

education: Academy of Fine Arts, University of Ljubljana, Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, Faculty for Mathematics and Physics, University of Ljubljana

lives and works in Cambridge and Ljubljana

The core of Tobias Putrih’s artistic practice is the interface between the concrete, man-made environment and its mental simulations. He reconsiders public spaces and objects defined by various concepts of architecture and design. Many of Putrih’s projects are collaborative, conceived in collaboration with architects, filmmakers, designers, art historians and computer programmers. The works become designs, maquettes or purely conceptual models. Temporary environments are constructed from paper, cardboard, plywood or light. In 2007 Putrih represented Slovenia at the Venice Biennale. His works have been presented in solo exhibitions at the Museum Boijmans Van Beunigen in Rotterdam, the MIT List Center in Cambridge, the Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Museum of Modern Art in Ljubljana.

Ardalan SadeghiKivi

*1995 (Iran)

education: School of Architecture and Planning, Massachusetts Institute of Technology / Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Tehran

lives and works: in Boston.

Ardalan SadeghiKivi, as an artist, designer, and computer programmer, probes and tests understanding of the computation embedded in everyday objects and interactions. His unique take on how computing distorts and manipulates our senses and beliefs is a guiding principle of his seemingly simple but highly elaborate and complex artworks. Programmed rocks, sound manipulated to influence outcomes, and nonsensical nanoscale objects are just a few strategies entangling imagination and computing, where technology is so deeply embedded into a matter that it becomes almost invisible. SadeghiKivi teaches at MIT, and his work spans diverse contexts, from art exhibitions to publishing and architectural interventions.

Tobias Putrih (with Ardalan SadeghiKivi) Green Groag, 2024

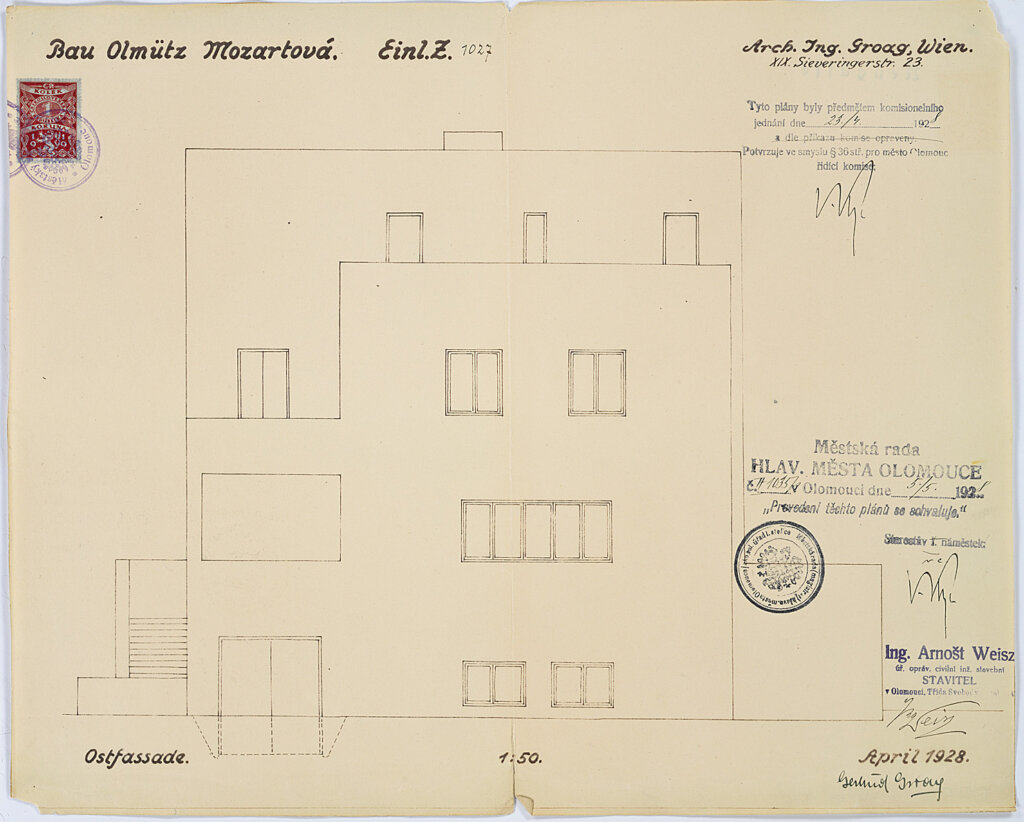

Jacques Groag worked as an architect on two seminal houses of late 1920s Vienna: the Moller House by Loos and the Stoneborough House by Ludwig Wittgenstein. If the old photographs of the Moller House interiors show a relatively restrained approach to decoration, the explicit formalism in Wittgenstein’s design is immediately contrasted by his sister’s penchant for collecting antiques. Both houses were designed with facades that acted as functional shells, creating secure, unregulated private spaces where the architects didn’t judge interior design choices. However, as Groag continued to design homes into the next decade, his interiors evolved to reflect a much more regulated modernist operation. House interiors started to mimic facades. This transformation in Groag’s work reflects a broader trend in modern homes, where technological advances and optimized production processes spurred the development of industrial design.

This tectonic shift is the focus of our project in Olomouc, which we could metaphorically describe as the Groag’s ‘crumbling monumentality.’ We juxtapose crumpled paper—originally shaped like Groag’s facade—with its digital simulation rendered through an intense green color. Our goal is simple: as a physical artwork, we want its images to disseminate serendipitously across the Internet. By tagging them with “Groag” metadata, we intend to shift the “Groag” digital identity as a concept in search engine databases from grayish-white to green. If web searching “Groag” today mostly returns black and white images, future updated search queries will result in thumbnails of multiple green digital “ghosts.” This endeavor balances the Groag facade’s monumentality with the seemingly nonsensical operation of turning “Groag” green.

Tobias Putrih is playing a highly intellectual game with the symbolic level of architecture and its modernist legacy. The notion of monumentality finds in the subtle nuances of its shifts in form and meaning. He is intrigued by the work of Jacques Groag (1892-1962), a Jewish architect from Olomouc, who was fortunate enough to survive the Holocaust and complete his Central European career with his wife Jacqueline in London.

Putrih in a dialog with the artist, architect and programmer Ardalan SadeghiKivi understand the monumentality of the abstract geometric modernist façade of the 1920s and 1930s not only in its formal refinement and forcefulness but also in the sense of the turn of meaning established by Groag’s teacher and colleague Adolf Loos. The mask of the façade becomes a monument, but it ceases to be the identity of the house’s inhabitants, as it had been in the decisively rejected Art Nouveau. The new monumentality (“monumentalisme”) lies in accepting the new function of the house mask as a protective wall, as a public declaration that the owner’s privacy is paramountly defended. The risk the architect takes lies in filling these invisible, private spaces with ballast and allowing the client’s misdirected taste to overrun the architectural form.

Tolerance for the individuality of the builder is ultimately trumped by mass-produced and mass-accepted objects of “modern” desire. The monumentality of monumental modernism becomes trivialized, crumbles. “Reproducibility calls into question the unique aura of the artwork, its ritual mystery, place of birth and monumental status,” says Putrih. His collaboration with SadeghiKivi is a new dialectical play between images and information, contrasting the uniqueness of the real with the simulation of images disseminated online.